In my May 24 blog entry on Counseling The Culturally Diverse, I developed an alternate plan for my study of Asian American Identity. I felt that the Sues' text just stated things that were obvious.

Quoting me: “...you can learn about people by being physically around them or by finding a way to immerse yourself in their worlds...” not by reading textbooks on race.

Rereading Nikki S. Lee was great. It made me experience this complex imaginative playfulness I haven't felt in a while. There is something so thoroughly manufactured and deliberate in her work, but also something so true. It was a great experience. Now in keeping with my plan, I'll read a bit of Toni Morrison.

In college, I remember there was a course being offered that read some of Toni Morrison's works alongside Moby Dick. Somehow, students were to come to see Melville's text as a complex comment on Blackness and Whiteness. The course was unavailable to freshman, so I never took it. I'm glad, now because I wouldn't have understood it at all. I eventually read Moby Dick on my own. I remember a very odd, morbid beginning, an unbelievably long middle and a suspenseful ending. Overall, the text had a scary and surreal feel to it.

It begins with Ismael and Queequeg getting married, there's a point where all off the men on the boat pull sperm out of a whale in this bizarre homoerotic bonding ritual, there are tons of references to Milton, to death, to Satan...it's odd. I couldn't figure out exactly what all of the text had to do with race, but I did get the idea of the text as an odd, complex dream. There is Blackness, Whiteness, slavery, colonialism, sex...it's all mixed up. It gave me the feeling that Melville was possessed when he wrote it. All of the ideas in his head sort of mixed in a giant cauldron and after letting the contents simmer for a few months, at the bottom, there was this novel.

Without entirely understanding what I read, or understanding what Morrison wished to say about it, in my mind, I developed an intuitive approximation of the text and Morrison's commentary. She saw something in this dream of Melville's that was not consciously racial, not with allegorical meaning, but somehow influenced by the absence of race. A child who loses a father at birth can have dreams where his missing parent's absence becomes a presence---a character, or a distinct set of feelings. This, I assumed to have occurred in Moby Dick. And I believe race in America to have these dreamlike, surreal, presence and non-presences. I've felt these presences in my own dreams, specifically, I can recall one that I had years ago that involved Bill Cosby coughing up blood. There was no direct allegorical meaning of the dream available to me. It is somehow affected by my odd unconscious American conception of race.

Now that I have the freedom to read what I want to, I figure it's time to finally take a look at Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature, a lecture delivered at the University of Michigan on October 7, 1988.

It seemed to me that the Sues simplified the lived experience of race and dumbed it down to put it into textbook format. Morrison doesn't do this at all. She explodes the contradictions within our ideas of race---amplifies the manifestations of racial thinking and unearths the way unconscious ideas of race inform our conceptions of the world. I wouldn't say it would be a good idea to ignore works like the Sues' or works like Morrison's.

In Morrison's lecture, criticism becomes a creative act. It's interesting for me to think that interpreting the world can require so much mental agility.

In the following key sections of her lecture, Morrison concisely explains the kind of reading she advocates:

“We can agree, I think, that invisible things are not necessarily 'not-there'; that a void may be empty but not be a vacuum. In addition, certain absences are so stressed, so ornate, so planned, they call attention to themselves; arrest us with intentionality and purpose, like neighborhoods that are defined by the population held away from them” (137).

I'll attempt to elucidate this point by reversing the structure of the metaphor:

Imagine, as Morrison does, a neighborhood defined by the population held away from it. I think of Jamiaca Plain in Boston. I can feel the presence of “invisible things” there very sharply. The exact geometry of the neighborhood is hard to explain, but Centre Street and Lamartine St. act as the primary invisible borders that separate the White world and the world of people of color. Although technically still part of Jamaica Plain, the worlds that lay on the sides of these borders are thought of as being part of Roxbury, a predominantly Arican-American and Latino neighborhood. What keeps White people in Jamaica Plain and people of color out? There is no specific mechanism that does this, to some degree these borders are porous. In Morrison's words, “...the void...” in these sections of the city “..is not a vacuum” Regardless of whether White people or people of color are in the neighborhood, what's experienced within these zones is a strong White cultural presence or a strong cultural presence of Non White people.

What creates these cultural presences and absences? Well, there are certain walking routes that lead toward public schools, some that lead towards upscale cafes and yoga studios. Some that lead to subsidized housing. Some that lead toward bus routes that extend to parts of the city unserved by the subway.

What would these absences consist of in a text? The places where the author unconsciously distorts reality because of the impact of something unbearable on her mind. What happens when the creators of texts are forced repress and distort memories to shield themselves from traumatic, painful realities.

Someone who can simply choose not to focus on painful things is functioning at a high enough level as to not be affected by the distorting factors Morrison discusses. She makes this clear when she tells us this when she is “not recommending an inquiry into the obvious impulse that overtakes a soldier sitting in a World War I trench to think of salmon fishing” (137). She is also not interested in asking 'why,' as 'an Afro-American,' she is 'absent' from the scope of American literature, as it is not a 'particularly interesting query (137). Instead, the “exploration” she suggests is one that asks

“...what intellectual feats had to be performed by the author or his critic to erase me from a society seething with my presence, and what effect has that performance had on the work? What are the strategies of escape from knowledge? Of willful oblivion?” (137).

What would happen if I were to ask myself these questions? What works of art have I seen recently that would be worthy of a Morrisonian reading? I don't have the brains or training to conduct the high level of literary analysis that Morrison performs on Melville. But if I look on the culture that I've consumed in the past few months...sort of try to re-dream the series of experiences I've had...let's see what I come up with.

Last night, I saw Super 8, the film by Steven Spielberg and JJ Abrams. I can't remember the specifics of the plot---they are unimportant. Aliens seemed to represent a force with the natural power of the tornadoes that hit Springfield Massachusetts and a violent, evil rhetoric to match that of Osama Bin Laden. I kept thinking that Abrams must have had Bradley Manning in mind when he wrote the script, as there was a consistent theme of capture and imprisonment, by both the aliens and the army. The only man who was able to make contact with the aliens was an African-American. There were two African American characters on screen. He was the victim of tremendous violence early in the film and died in the middle. The other African American was killed quickly, as dictated by racist Hollywood cliché, the first in his group to be laid to waste. I'm lead to wonder, were these sort of sacrificial Christ figures, or victims of a collective desire to see African-Americans get hurt onscreen?

While JJ Abrams talents as a writer cannot compare to Melville 's, his work is similar to Moby Dick in its level of confusion and disruption. Abrams does not attempt to create an allegorical film, but it is clear that events carrying unbearable psychic weight bared upon his mind when creating the film. The presence of Al-Qaeda, the effects of global warming on the environment, the US government's treatment of suspected terrorists---all of these things are on his mind, and come out in a twisted, distorted form in his work. Morisson would want to know---what specific “intellectual feats” displace race from the text? Unfortunately for the symmetry of my analysis, I believe that it is an escapist, racist desire for an all White world that eliminates an African American presence in the text rather than deep pressures weighing on the author. “Intellectual feats” are not abundant in Abrams's work. Anyone who has seen Lost can attest to this.

I'm hard pressed to find an example of a contemporary author's “intellectual feats” in distorting a text---this is something that I will continue to look for. Would people have to be living in a time where historical forces have more of an effect on their day to day lives in order for these “feats” to be performed?

The presence of “invisible things” is always around me. I remember feeling it in particular at a Red Sox game I went to last month. Prior to the singing of the Star Spangled Banner, a few African-American students were on the JumboTron being honored for winning an academic prize. As the camera panned in on their faces, the announcer made several explicit references to the fact that these “disadvantaged” students were winning awards for “underprivileged” students. I could see the award winners faces sour when this announcement was made. At this moment, they ceased being proud scholars, and became objects of the audience's charity.

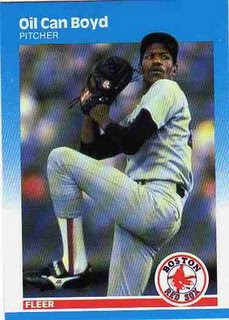

The ballpark was filled with White people. I thought of Boston's history as a racist, White city, of Oil Can Boyd's mistreatment when I was a kid and the racist legacy of the Red Sox, of the split I've noticed between Massachusetts Latinos who root for the Yankees and Whites who root for the Sox, of the few people of color in the audience and what they must have been thinking, of the failure of civil rights, of the inequalities in Boston Public Schools, of bussing,...all of this comes up. It's unnamed, yet it's presence undoubtedly exists. Morrison gives words to the experience of living with this presence.

My analysis sounds crazy? I'm not so out of line in applying these ideas to my own day to day life. According to Morrison, Melville was “Overwhelmed by the philosophical and metaphysical inconsistencies of an extraordinary and unprecedented idea that had its fullest manifestation in his own time in his own country...” (142). Slavery ended less than 150 years ago. It is easy to imagine that Morrison would imagine Americans in 2011 to still feel the impacts of this massive cultural disruption.

Her interpretation of Melville makes him seem quite contemporary and relevant. At the end of this exercise, I'm left wondering, though why Morrison winds up feeling so dated. Although we may live in this chaotic sea of shifting, wrenching cultural meanings, must people seem to feel pretty much okay. Despite whatever 'complex interplay between signs' we may have been witnessing at Fenway park, everyone seemed to be pretty much having a good time. To study the areas in which race disappears because of its overwhelming presence---this is a taxing endeavor! There is something so attractive about this complex way of thinking about race, but ultimately, if you engage in this practice, you either get a PHD or go mad---two options not available for the average person. I'm searching for a balance between this way of thinking and that of the Sues'. It would be forcing a false structure on her work to pose Nikki Lee as doing this, however convenient it may be for me to do so.

I'm looking for a way of thinking about race that is both pragmatic for day to day life, like the Sues' and creative like Morrison's. This search will continue in this blog.